Does Everything We Find Somewhere Constitute Our “Historical Reality”?

This argument lacks solid logic, and those who make this argument overlook the principles of historical, archival, and archiving research entirely

In his novel “1984,” George Orwell writes: “Who controls the past controls the future. Who controls the present controls the past.” It’s easy to say that this book merely collects documents and reports the “historical reality” without analyzing it. But the crucial question is: What is historical reality, and how do we understand it? Does any document we gather from anywhere necessarily constitute our historical reality? What is the relationship between these documents, colonial power relations, and our lived historical reality? How can we comprehend these relationships? What is an archive? How is it created? What is its relationship to power? What is its relationship to the lived historical truths of various peoples? And countless other vital questions ...

Simply collecting documents, in itself, has no intrinsic value. Researching archives and searching for historical reality among these documents have their own methods. For example, why and how are these specific documents chosen from among so many different ones to be included in a collection? This is part of the methodological logic. Collecting documents must have a clear objective, and primarily, these documents already exist in archives and do not need to be collected if they do not fulfill a specific purpose. These documents are safe from needing to be collected and scattered. They are all kept organized and categorized. All documents are well placed. Collecting and referring to them only makes sense if we aim to answer specific questions with their help.

Our society today has access to academic knowledge and standards. We must align ourselves with these standards. Our current generation should not look at history and archival works according to the standards of Qom from decades ago. We need to hold the standards in our hands. We must understand what standards are prevalent and utilized in today’s history and archival work departments. We need to align ourselves with these standards and critically engage with them, choosing our working tools consciously and critically.

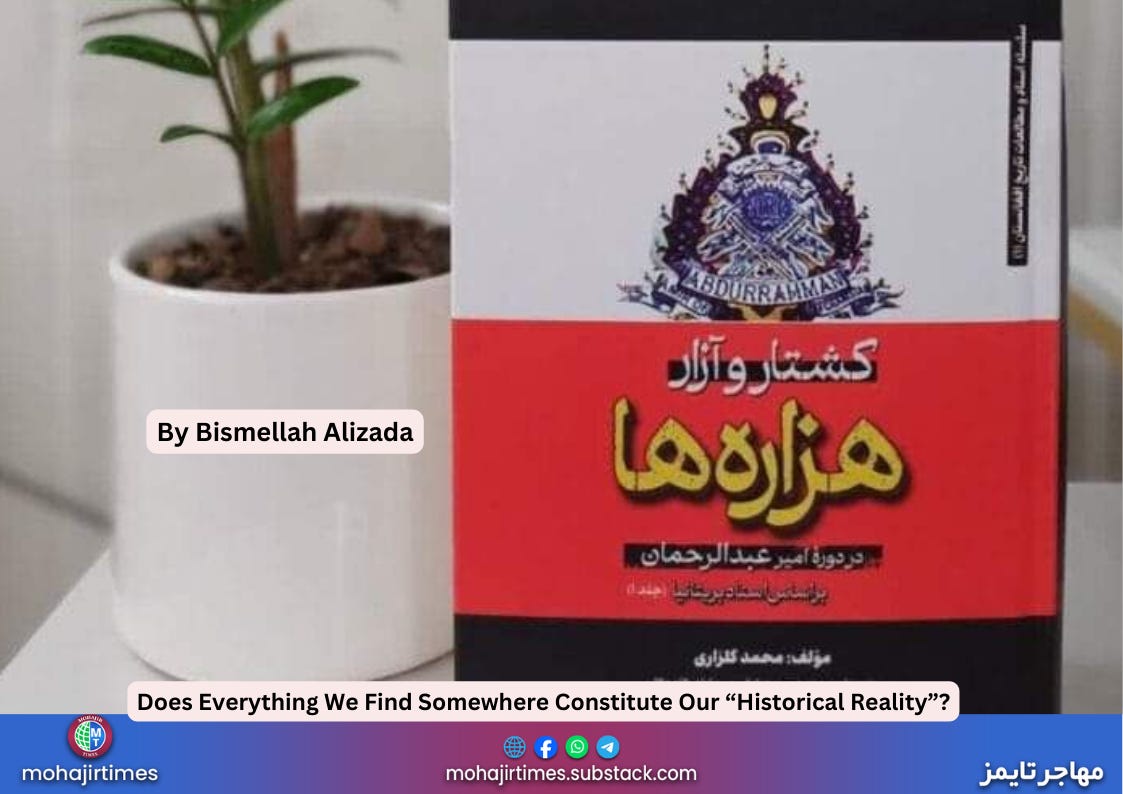

When we access these resources, we must not deceive ourselves into thinking our work is unscientific and that we are amateurishly collecting documents. History is no joke and cannot be treated trivially. Regarding a historical topic like what happened to the Hazaras at the end of the nineteenth century, one cannot work trivially or collect documents out of sheer enthusiasm. This subject is serious, and its work must be done with proper and acceptable tools.

We must ask ourselves how these documents can be understood, explained, and interpreted-translated. Documents are fossilized forms of power relations, and power lives in these documents. Colonial archival documents were created and maintained by colonial powers and have reached us. How much understanding and access did the colonial scribes have to the situation of the Hazaras, and how critical was the problem of the Hazaras to them? What did they overlook, and what did they reflect? What was their purpose? How much of the lived reality of the Hazaras in that historical period can these documents convey? It is not that we should wholly accept everything in these documents as our historical reality and collect it with this presumption, turning it into a taboo …

Again, I emphasize that we cannot collect any document in any manner and present it as the “historical reality” of the people. This grand claim that the “historical reality” lies in these documents must be proven. A reader of this book will not find satisfactory answers to important questions about that part of the Hazaras’ history within these documents. For instance, what happened to the Hazaras genocide? These documents do not show anything specific. What was the excommunication of the Hazaras, how was it carried out, who wrote it, and what was its relationship with power in Kabul? What is mentioned in these documents is misleading.

The documents state that a “Khany Mullah,” whose identity is unclear, wrote it or that there were between 15 to 20 excommunication letters. These all lack proper historical basis. How many Hazaras were killed or sold into slavery? These documents do not provide a specific answer to this question. How much of the Hazaras’ land was taken from them? This question is also not answered in these documents. In this book, which the author claims is not an analysis, the massacre of the Hazaras is analyzed as part of the “Great Game.” How can such a document be valid for our history and uncover or prove historical realities? What objective can haphazardly collecting such records serve?

Another argument is that the work has been made easier for other researchers. This argument lacks solid logic, and those who make this argument overlook the principles of historical, archival, and archiving research entirely. No researcher can refer to this book, and for archival work, it is necessary to go directly to the archives and see the documents first-hand before referencing them. We live in a world where “Masterful Forgery” or Deep Fake is commonplace. These documents cannot be referenced in such a specific situation, especially since they have been translated into another language and the publisher has no credibility.

Why should we turn first-hand archival documents into second-hand documents and then claim that the work has been made more accessible for future generations and that they can reference them as research sources? Significantly, since the author of this book has arbitrarily cut the documents. He has brought one document in its entirety, included a paragraph from another document that contained the word Hazara and omitted the rest, and from other documents, he has brought small snippets and left out the rest …

One contribution this book and the collected documents in it make is to convince the reader that the “Great Game” was at play between the powers; the Hazaras were also victims of this game, and because they were allied with the Russian and Iranian armies, the British felt threatened and helped Abdur Rahman suppress these people. Nothing major has happened. And this book shows this. Is this our historical reality? It is interesting to see the lives and existence of the Hazaras as victims of the Great Game between the British and the Russians and then believe that the British archives have collected and preserved the historical realities related to it!

Thus, not every document is a historical reality, and not every action helps us reach historical truth. We must modernize our understanding of history and historical reality and equip ourselves with the necessary intellectual, research, and ethical tools for such work. Our current generation must hold these standards in their hands.

In any case, I am glad that Yahya Erfan has taken the time to review and evaluate my critique. One of my purposes in writing that critique was to spark a discussion and debate on this issue. I leave the reading and judgment of the text to interested readers.

Memo: “Literary Criticism” differs from criticism in other fields, such as history.